We can’t fight climate change without understanding what drives it

At the root of climate change is the phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect, the term scientists use to describe the way that certain atmospheric gases “trap” heat that would otherwise radiate upward, from the planet’s surface, into outer space. On the one hand, we have the greenhouse effect to thank for the presence of life on earth; without it, our planet would be cold and unlivable.

But beginning in the mid- to late-19th century, human activity began pushing the greenhouse effect to new levels. The result? A planet that’s warmer right now than at any other point in human history, and getting ever warmer. This global warming has, in turn, dramatically altered natural cycles and weather patterns, with impacts that include extreme heat, protracted drought, increased flooding, more intense storms, and rising sea levels. Taken together, these miserable and sometimes deadly effects are what have come to be known as climate change.

Detailing and discussing the human causes of climate change isn’t about shaming people, or trying to make them feel guilty for their choices. It’s about defining the problem so that we can arrive at effective solutions. And we must honestly address its origins—even though it can sometimes be difficult, or even uncomfortable, to do so. Human civilization has made extraordinary productivity leaps, some of which have led to our currently overheated planet. But by harnessing that same ability to innovate and attaching it to a renewed sense of shared responsibility, we can find ways to cool the planet down, fight climate change, and chart a course toward a more just, equitable, and sustainable future.

Here’s a rough breakdown of the factors that are driving climate change.

Natural Causes of Climate Change

Some amount of climate change can be attributed to natural phenomena. Over the course of Earth’s existence, volcanic eruptions, fluctuations in solar radiation, tectonic shifts, and even small changes in our orbit have all had observable effects on planetary warming and cooling patterns.

But climate records are able to show that today’s global warming—particularly what has occured since the start of the industrial revolution—is happening much, much faster than ever before. According to NASA, “[t]hese natural causes are still in play today, but their influence is too small or they occur too slowly to explain the rapid warming seen in recent decades.” And the records refute the misinformation that natural causes are the main culprits behind climate change, as some in the fossil fuel industry and conservative think tanks would like us to believe.

Human-Driven Causes of Climate Change

Scientists agree that human activity is the primary driver of what we’re seeing now worldwide. (This type of climate change is sometimes referred to as anthropogenic, which is just a way of saying “caused by human beings.”) The unchecked burning of fossil fuels over the past 150 years has drastically increased the presence of atmospheric greenhouse gases, most notably carbon dioxide. At the same time, logging and development have led to the widespread destruction of forests, wetlands, and other carbon sinks—natural resources that store carbon dioxide and prevent it from being released into the atmosphere.

Right now, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide are the highest they’ve been in the last 800,000 years. Some greenhouse gases, like hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HFCs), do not even exist in nature. By continuously pumping these gases into the air, we helped raise the earth’s average temperature by about 1.9 degrees Fahrenheit during the 20th century—which has brought us to our current era of deadly, and increasingly routine, weather extremes. And it’s important to note that while climate change affects everyone in some way, it doesn’t do so equally: All over the world, people of color and those living in economically disadvantaged or politically marginalized communities bear a much larger burden, despite the fact that these communities play a much smaller role in warming the planet.

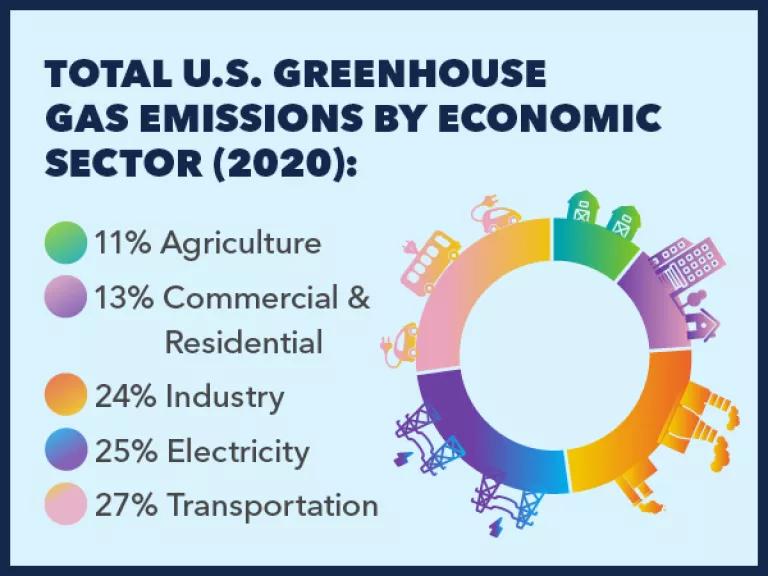

Our ways of generating power for electricity, heat, and transportation, our built environment and industries, our ways of interacting with the land, and our consumption habits together serve as the primary drivers of climate change. While the percentages of greenhouse gases stemming from each source may fluctuate, the sources themselves remain relatively consistent.

Transportation

The cars, trucks, ships, and planes that we use to transport ourselves and our goods are a major source of global greenhouse gas emissions. (In the United States, they actually constitute the single-largest source.) Burning petroleum-based fuel in combustion engines releases massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Passenger cars account for 41 percent of those emissions, with the typical passenger vehicle emitting about 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. And trucks are by far the worst polluters on the road. They run almost constantly and largely burn diesel fuel, which is why, despite accounting for just 4 percent of U.S. vehicles, trucks emit 23 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

We can get these numbers down, but we need large-scale investments to get more zero-emission vehicles on the road and increase access to reliable public transit.

Electricity generation

As of 2021, nearly 60 percent of the electricity used in the United States comes from the burning of coal, natural gas, and other fossil fuels. Because of the electricity sector’s historical investment in these dirty energy sources, it accounts for roughly a quarter of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.

That history is undergoing a major change, however: As renewable energy sources like wind and solar become cheaper and easier to develop, utilities are turning to them more frequently. The percentage of clean, renewable energy is growing every year—and with that growth comes a corresponding decrease in pollutants.

But while things are moving in the right direction, they’re not moving fast enough. If we’re to keep the earth’s average temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, which scientists say we must do in order to avoid the very worst impacts of climate change, we have to take every available opportunity to speed up the shift from fossil fuels to renewables in the electricity sector.

Industry & Manufacturing

The factories and facilities that produce our goods are significant sources of greenhouse gases; in 2020, they were responsible for fully 24 percent of U.S. emissions. Most industrial emissions come from the production of a small set of carbon-intensive products, including basic chemicals, iron and steel, cement and concrete, aluminum, glass, and paper. To manufacture the building blocks of our infrastructure and the vast array of products demanded by consumers, producers must burn through massive amounts of energy. In addition, older facilities in need of efficiency upgrades frequently leak these gases, along with other harmful forms of air pollution.

One way to reduce the industrial sector’s carbon footprint is to increase efficiency through improved technology and stronger enforcement of pollution regulations. Another way is to rethink our attitudes toward consumption (particularly when it comes to plastics), recycling, and reuse—so that we don’t need to be producing so many things in the first place. And, since major infrastructure projects rely heavily on industries like cement manufacturing (responsible for 7 percent of annual global greenhouse gas), policy mandates must leverage the government’s purchasing power to grow markets for cleaner alternatives, and ensure that state and federal agencies procure more sustainably produced materials for these projects. Hastening the switch from fossil fuels to renewables will also go a long way toward cleaning up this energy-intensive sector.

Agriculture

The advent of modern, industrialized agriculture has significantly altered the vital but delicate relationship between soil and the climate—so much so that agriculture accounted for 11 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. This sector is especially notorious for giving off large amounts of nitrous oxide and methane, powerful gases that are highly effective at trapping heat. The widespread adoption of chemical fertilizers, combined with certain crop-management practices that prioritize high yields over soil health, means that agriculture accounts for nearly three-quarters of the nitrous oxide found in our atmosphere. Meanwhile, large-scale industrialized livestock production continues to be a significant source of atmospheric methane, which is emitted as a function of the digestive processes of cattle and other ruminants.

But farmers and ranchers—especially Indigenous farmers, who have been tending the land according to sustainable principles—are reminding us that there’s more than one way to feed the world. By adopting the philosophies and methods associated with regenerative agriculture, we can slash emissions from this sector while boosting our soil’s capacity for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, and producing healthier foods.

Oil & Gas Development

Oil and gas lead to emissions at every stage of their production and consumption—not only when they’re burned as fuel, but just as soon as we drill a hole in the ground to begin extracting them. Fossil fuel development is a major source of methane, which invariably leaks from oil and gas operations: drilling, fracking, transporting, and refining. And while methane isn’t as prevalent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide, it’s many times more potent at trapping heat during the first 20 years of its release into the atmosphere. Even abandoned and inoperative wells—sometimes known as “orphaned” wells—leak methane. More than 3 million of these old, defunct wells are spread across the country and were responsible for emitting more than 280,000 metric tons of methane in 2018.

Buildings

Unsurprisingly, given how much time we spend inside of them, our buildings—both residential and commercial—emit a lot of greenhouse gases. Heating, cooling, cooking, running appliances, and maintaining other building-wide systems accounted for 13 percent of U.S. emissions overall in 2020. And even worse, some 30 percent of the energy used in U.S. buildings goes to waste, on average.

Every day, great strides are being made in energy efficiency, allowing us to achieve the same (or even better) results with less energy expended. By requiring all new buildings to employ the highest efficiency standards—and by retrofitting existing buildings with the most up-to-date technologies—we’ll reduce emissions in this sector while simultaneously making it easier and cheaper for people in all communities to heat, cool, and power their homes: a top goal of the environmental justice movement.

Deforestation

Another way we’re injecting more greenhouse gas into the atmosphere is through the clearcutting of the world’s forests and the degradation of its wetlands. Vegetation and soil store carbon by keeping it at ground level or underground. Through logging and other forms of development, we’re cutting down or digging up vegetative biomass and releasing all of its stored carbon into the air. In Canada’s boreal forest alone, clearcutting is responsible for releasing more than 25 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year—the emissions equivalent of 5.5 million vehicles.

Government policies that emphasize sustainable practices, combined with shifts in consumer behavior, are needed to offset this dynamic and restore the planet’s carbon sinks.

Our Lifestyle Choices

The decisions we make every day as individuals—which products we purchase, how much electricity we consume, how we get around, what we eat (and what we don’t—food waste makes up 4 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions)—add up to our single, unique carbon footprints. Put all of them together and you end up with humanity’s collective carbon footprint. The first step in reducing it is for us to acknowledge the uneven distribution of climate change’s causes and effects, and for those who bear the greatest responsibility for global greenhouse gas emissions to slash them without bringing further harm to those who are least responsible.

The big, climate-affecting decisions made by utilities, industries, and governments are shaped, in the end, by us: our needs, our demands, our priorities. Winning the fight against climate change will require us to rethink those needs, ramp up those demands, and reset those priorities. Short-term thinking of the sort that enriches corporations must give way to long-term planning that strengthens communities and secures the health and safety of all people. And our definition of climate advocacy must go beyond slogans and move, swiftly, into the realm of collective action—fueled by righteous anger, perhaps, but guided by faith in science and in our ability to change the world for the better.

If our activity has brought us to this dangerous point in human history, breaking old patterns can help us find a way out.

Source: NRDC