Interview with John Doerr and Ryan Panchadsaram’s on their new book “OKRs to get to Net Zero”

Interview by Kim Zou, Sophie Purdom November 19, 2021

Author John Doerr is perhaps best known for his 40+ year long career at Kleiner Perkins during which he backed Google and Amazon early on, alongside a cohort of Clean Tech 1.0 companies. KP was subsequently beaten up in the press during the CT1.0 bust, but as John remarks in the Prologue, “We stood by our founders. By 2019, our surviving cleantech investments began to hit one home run after the next. Our $1b in green venture investments is now worth $3b.”

John and his coauthor, Ryan Panchadsaram, proudly tout an ‘engineering mindset’ and apply appropriately structured rigor to this book for a course of action to reach net zero by 2050. Given the constantly evolving nature of the climate crisis, John and Ryan decided to make the book a living, breathing source of reference. To be updated on a yearly basis, Speed and Scale will constantly reflect the ongoing efforts, success stories and necessary steps to net zero. Whizzing through the pages, recognizable faces pop up from founders & CEOs (Ryan Popple, Lynn Jurich, Bill Gates) to policymakers (John Kerry, Al Gore) to investors (Larry Fink, Carmichael Roberts). They share their anecdotes, words of wisdom, and forecasts for the future and invite readers to pick their climate plan.

Speed & Scale’s approach draws heavily on their previous book, Measure What Matters, in which the authors preach that “Ideas are easy. Execution is everything.” Their mantra? Objectives and Key Results (OKRs).

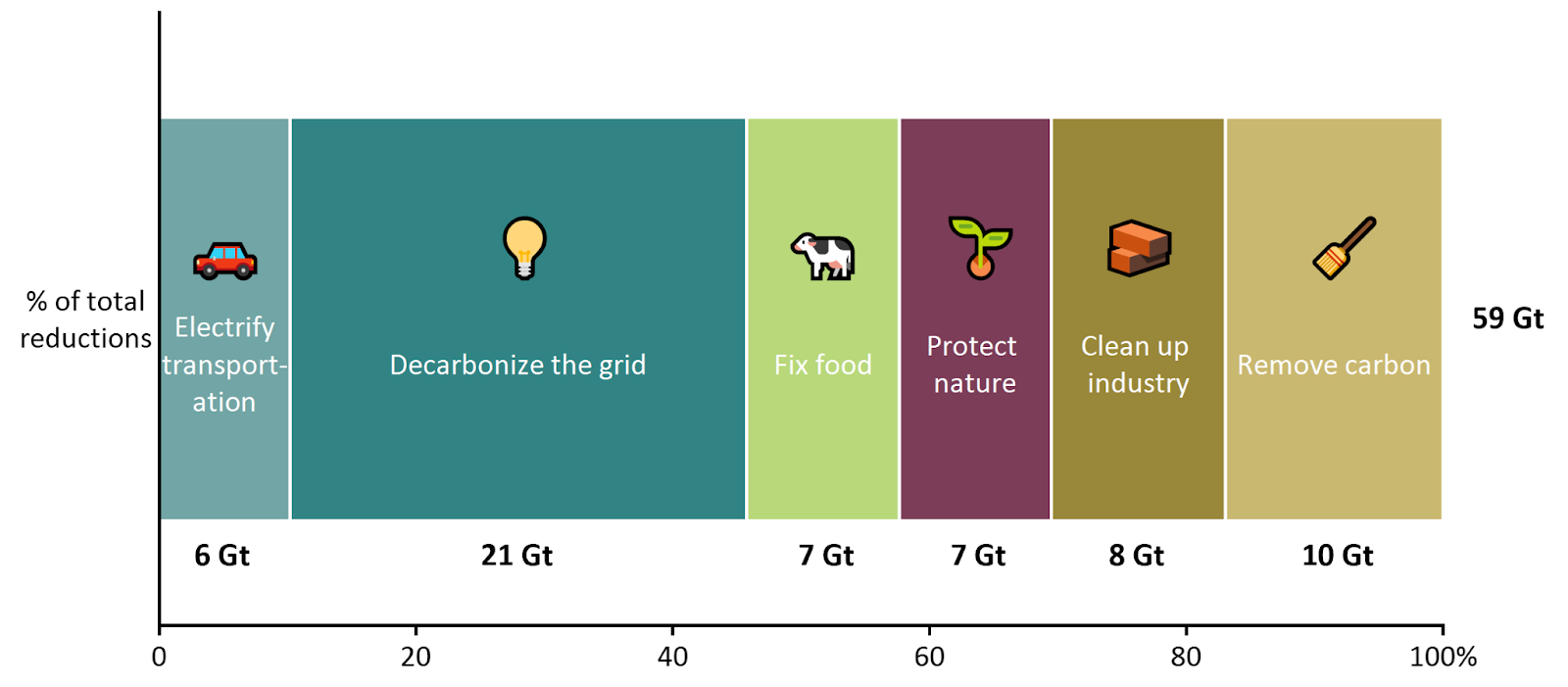

In the goal-setting tool, the Os are what you aim to accomplish and the KRs tell us how we’ll get the objectives done. Within each chapter, OKRs break down specific actions to accomplish quantified reductions of the 59 Gigaton countdown to net zero.

Spiral-bound advanced copies in hand, we got to know the people behind the plan, and why they think that OKRs are the antidote to CO2.

Q&A with Ryan Panchadsaram

What’s the story behind Speed & Scale? How did you and John come together to collaborate on developing this climate action plan?

John and I met when I was an entrepreneur in residence at Kleiner. When John became Chairman, he was looking for a partner to work with him that had a background in engineering, government, and healthcare – I happened to check those boxes – so I leapt at the opportunity.

The spark for Speed & Scale came two years ago when we asked: what it would look like to apply OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) to the climate crisis. As investors and engineers ourselves, we are forever learners. So we kicked off conversations with leading scientists, entrepreneurs, and founders trying to tackle climate change. We were on the ground trying to uncover what drives emissions at the gigaton level and what levers could pull that down. Just as those conversations educated us, we realized they could also help educate the world. Since all of this was happening in Zoom world, it was easy for us to record and capture those stories. .

What’s different about Speed & Scale compared to other climate solutions books like Drawdown?

We are in awe of the literature that exists in the climate space. In my room right now, there are dozens of books on climate – from Elizabeth Kolbert’s books to Bill Gates’ How to Avoid a Climate Crisis to the collection of leaders in All We Can Save. Then you have Drawdown which is a list of solutions that we refer to a few times in Speed & Scale. When we read through all of these books we came with the same question: what’s the plan and how do the numbers add up? Speed & Scale tries to answer that through our research and the 100+ interviews we conducted.

We also focus on the impact of policy, activism, innovation, and investment and how these four levers can accelerate the pace of emissions reductions. Many of the great climate books were written several years ago when VCs were spending as little as $2 billion a year on climate tech and before we had Proterra, Beyond Meat, or Sunrun. Now VCs are deploying almost $30 billion this year. We wanted the book to capture the fire and spirit of the current moment.

Your book takes a page out of how C-Suite execs think about growth by using OKRs. What are OKRs and how do they fit into the context of addressing the climate crisis?

Simply put, OKRs are a goal setting system, a succinct way of saying: This is where we’re going to go and what it means to get there.

John is famous as an investor but he is also famous as the Johnny Appleseed of OKRs. The first book we worked together on, Measure What Matters, was about OKRs. John first learned about OKRs from Andy Grove, the CEO of Intel. As an engineer at Intel, John used OKRs as his method of managing and setting goals – keeping it inspirational but concrete. John then used OKRs to run his own company and then as an investor at Kleiner. He taught the concept to Google’s founders back when they were a company of 20.

On the heels of publishing Measure What Matters we began to ask ourselves what it would look like to apply OKRs to humanity’s biggest challenges. In the case here, climate was the lens. If our objective is to go from 59 to 0 gigatons, what OKRs do we have to set to get there?

The six solutions – electrifying transportation, decarbonizing the grid, fixing food, protecting nature, cleaning up industry, and removing carbon – get us to zero but that might take 100 years. So how do we get there in two or three decades? That’s where the next four OKRs, the accelerants, come into play in part II of the book. Each of the objectives have key results that act as warning signals, allowing us to track whether we reached the necessary goal to achieve net zero by 2050.

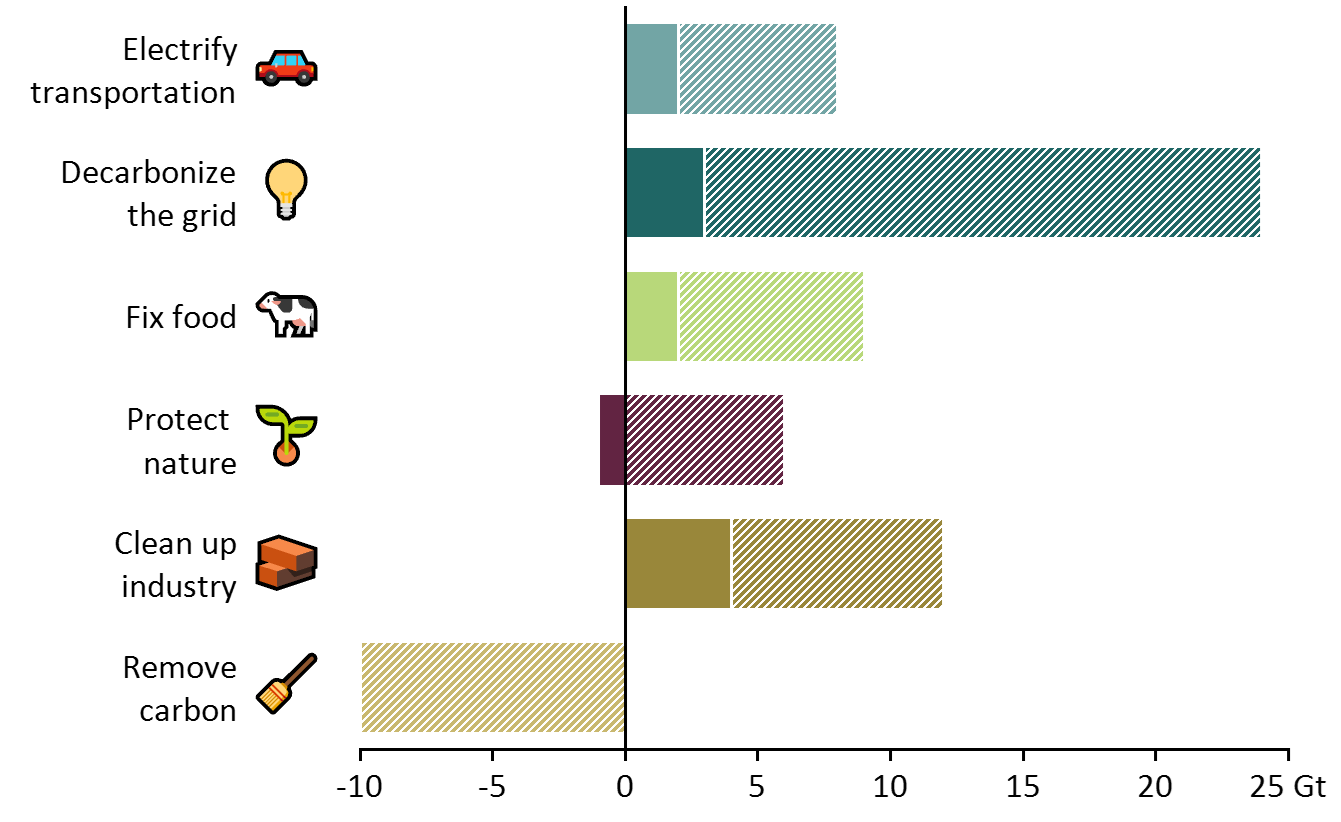

Let’s take electrifying transportation as an example. To succeed on that OKR you need to cut 6 gigatons of emissions. In that OKR there is a KR that serves as an early warning signal if EVs are not cheaper than their combustion engine equivalent. Then there’s the golden metric in electrifying transportation – the percent of miles driven that are electric versus non-electric. If we can take the number of fossil fuel-powered car miles down to zero then we have achieved our gigaton level ambition.

What are the OKRs you believe will be hardest to achieve?

Well, I can give you John’s answer and then I will give you my answer.

John’s answer is KR 6.2, Engineered Removal (Remove Carbon). So far, this industry has put 5,000 tons of carbon into the ground. We need to get to 5 billion tons by 2050. So from the glass half empty point of view, if we need 5 billion tons a year we would be running the entire oil system and then some in reverse. But, from the glass half full point of view you can have hope that since we’ve done that system one way, we can do it in reverse.

My answer is KR 4.1, Ending Deforestation. I choose this KR because when you think about going for the gigatons it would be deforestation. Unlike electrifying transport or making sustainable jet fuel, I don’t think engineering ingenuity or markets have the same role in this transition. Protecting nature is incredibly difficult. People cut down forests for their survival – they do it to grow food and to sell things. Tackling this problem will require wealthier nations to help poorer nations manage their forests and enforce bans. That’s a hard human problem.

Carbon dioxide removal (CDR) has been pointed out by the IPCC as a necessary component of staying to 1.5ºC warming. Your book outlines 10+ CDR approaches. Which do you view as most promising and why?

We never intended to have carbon removal as an Objective. But we realized that even if you assume the best case scenarios for the other five Objectives, it’s still not enough. There’s a reason the IPCC report calls for CDR. No matter how aggressive we are on cutting emissions, we still have to remove carbon.

We wanted to present this solution last for a reason. You see the Shells of the world highlighting their offset initiatives and carbon capture technology. There’s a whole category of CDR that’s just greenwashing. The only kind of carbon offsets that should count are true carbon removal – high quality nature-based and engineered removal which are additional, not just a project that was already underway. Nature-based removal lasts somewhere between 40 to 80 years and engineered methods last 1,000+ years. Microsoft’s report on the carbon offsets they pay for outlines the temporal differences between those nature versus engineered carbon removal methods.

There are several solutions that give me hope – massive projects in direct air capture (DAC) like Climeworks and Carbon Engineering, or bio-oil approaches like Charm Industrial. Charm takes biomass and – instead of letting it decompose and release emissions – turns it into bio-oil that is pumped underground. My prediction is that there are going to be several approaches to carbon removal. Charm is a great solution for countries with high ag waste, but another solution might work better for a country with different energy resources or waste products. The list of companies working on alternative solutions to carbon capture isn’t just 1 or 2, it’s now 15 or 20. These companies were catalyzed by companies like Microsoft and Stripe willing to pay a green premium and provide a few million to incentivize founders to start companies in the CDR space.

Your book + Bill Gates’ book both focus on this concept of a green premium. How realistic is it that industrial incumbents or even end consumers will pay up for “green”? What work is being done to close the gap?

The green premium is the added cost of cleaner, greener things. The term was coined by Bill Gates and comes from his hyperfocus that the role of innovation is to drive down the green premium. Will people pay for the green premium? Simply, no. Kleiner hit lots of losses initially in their early climate investments because of the green premium. The “but” though, is that there are a few categories where people will pay up and that’s usually where performance, beauty, and food play a role. Even then, cost still matters, and the green premium can be adjusted using incentives and taxes or by companies willing to pay for it because it’s the right thing to do.

I like to build on Gates’ green premium with the theory of the green discount: as costs are driven down by demand and innovation you eventually get to a cheaper green product. We see that now with solar and wind. The reason why there’s so much wind and solar is because as demand has surged, cost has been driven down. When the green premium hits zero, and then inverts into a green discount, market forces will make the transition to clean energy unstoppable.

In cases where the premium is still real, like direct air capture or sustainable jet fuel, programs like Breakthrough Energy’s Catalyst Fund are critical. They organize a group of willing actors to pay the green premium and drive the cost down. John likens this idea to the internet in the 90s. He used to say publicly that the internet is underhyped and folks would look at him like he was crazy. John believes the same thing is happening in climate tech. Right now we’re looking at companies like Charm removing 5,000 tons of CO2 this year and that costs a lot. But what about when we get to 100,000 tons or 1 billion tons? Costs will go down.

We loved the personal stories of leaders in the climate tech revolution and how each played a part in the OKRs needed to complete the plan. How did you identify the key folks to talk to? What were some of the stories that specifically stood out to you?

The stories we chose are the stories of the doers. We sought out the movers and shakers who can show us what is possible.

In the first chapter you meet Ryan Popple, an Iraq War vet that saw the toll of oil reliance in the Middle East and vowed to bring sustainable energy stateside. That led him to becoming the CEO of Proterra. In the next chapter you meet Lynn Jurich, CEO of Sunrun, who was inspired to deploy solar after her time in China where she witnessed their massive deployment of renewables and thought the same could be done in the US. Today Sunrun is a $12 billion company. Henrik Poulson of Orsted is another great leader. Orsted was an oil and gas company that got beat out by fracking in the US and so turned to wind. They leveraged their experience with offshore oil and gas to create an offshore wind business. Within four years, they cut the cost of wind deployment by 60%. Today they’re worth over $50 billion.

You also get to meet policy movers like Christiana Figueres and movement generators like Bruce Nilles who led the Beyond Coal campaign. In the investment chapter you hear how capital can accelerate the change we need, but you also learn lessons from John and Kleiner’s experience with CT1.0. (The guts and persistence it takes!) I hope when people flip through the pages of Speed & Scale to understand the plan, they’ll also find new role models of organizations and people to aspire to.

Your book (rightfully) points to solutions to mitigate the impact of climate change. When should we start thinking about technologies for climate adaptation and what are examples?

One of the hard realities of adaptation is that there is no strong business model for it. Our book focuses on mitigation and carbon cutting. We don’t ignore the question of adaptation, we just stay laser focused on cutting, cutting, cutting so that if done successfully, the adaptation part won’t be as bad. Adaptation could be an entirely new book where each chapter would discuss strategies for resilience. A book on adaptation would answer questions like what does transportation look like in a world with stranger weather patterns? What does the grid look like? It would also need to discuss the challenges of food, displacement, and climate refugees – all of which are challenges today and will only worsen as the world gets hotter.

Because we recognize the climate challenge will shift over time, we plan to update the book every year. We also hope to create a version for China, India, Europe, and even Russia – where the gigatons of emissions are.

Speaking of global challenges, what was it like being on the ground at COP? How do the COP commitments stack up to the key results you outlined? Where were you impressed and where did you wish to see more?

COP was electrifying – the passion for the delegates, the passion of the people and youth on the streets. But the activists and delegates at COP are seen as clashing parties. The activists’ job is to set the bar as high as they can, because ultimately the promises and pledges at COP are just that, pledges. Now the real test happens. As delegates return to their countries, it’s up to governments and businesses to support the pledges made at COP.

Another thing to keep in mind is that Winning Policy and Politics is just one of the OKRs. We have three other levers to pull. That’s why Greta Thunberg, Vanessa Nakate, and all of the youth activists are so important – they will help make climate a number one voting issue so we elect leaders who care about climate. If leaders care about climate, then they’ll make the pledges and commitments needed to drive down emissions.

In the concluding chapter of the book, you write, “If this book scares you into action, if it makes you as fearful as I am, then I have done my job. But for our fear to work for us, it needs to galvanize, not paralyze.” There is a thin line between galvanizing and paralyzing climate action. What strategies do you use to galvanize as opposed to paralyze?

The paralyzing part of the book is the first couple of pages where we acknowledge the problem. We’re very specific about what the problem is: it is not just a climate crisis, it’s an emissions crisis.

While individual action – switching to EVs, eating less beef and dairy, recycling, etc. – is expected, our book is focused on collective action. The big picture goal is cutting emissions at the systems level. We want folks to go to their city councils and press for clean grids and then to vote to ensure the funding is there. We want people to push for electric buses or protected bike lanes. This is the type of collective action that can draw down gigatons faster than individual action. The first part of the book is identifying where the emissions are coming from so you can understand where your time is best served at the gigaton level. In the second part of the book, the accelerants show where we can step in at the action level. As John says, ideas are easy, executing is everything.

What lessons do you hope today’s climate founders and investors take from Speed & Scale? How does venture capital play a role in the speed & scale of decarbonization?

We need the now and the new. We have 80% of the solutions we need to tackle our climate crisis. We need to deploy them aggressively at scale. The cost of wind and solar is continuing to go down, the same is happening for lithium ion batteries. We’re getting more out of electric vehicles and the grid is getting cleaner. Those are the low hanging fruit and if we implement them over the next decade that can get us halfway to net zero. But then there is the new technology which represents the 20% of solutions we don’t yet have, things like sustainable jet fuel or long duration batteries. These solutions require invention and investment. We need the next Teslas, Sunruns and Orsteds of the world to solve those challenges. To me, that’s also the exciting part – the whole world of innovators that will help us achieve the plan.

Where are you both today in helping to achieve these climate OKRs?

For John and I, the OKRs capture a plan we can act on. Now, we are asking ourselves how we can best deploy our capital into investing, philanthropy, and advocacy to take on the OKRs. We’re going to fund the companies that are bringing down emissions and support nonprofits that are moving the needle on climate. Supporting people is our priority. We hope that by sharing the OKRs with the world, people will take on these OKRs as well.

In writing the book we became humbled by the challenge of drawing down 59 gigatons of emissions. Each ton of emissions represents someone else’s business which means someone on the other side is fighting to keep those emissions alive. There will be winners and losers, but if we do our part really well as founders, policymakers, activists, and investors, we will win.

Source: CTVC